Habonim Dror United Kingdom Yom Hashoah Tekkes 2020:

Remembering Through Memory

On Tuesday 21stApril, Habonim Dror came together with members, alumni and parents to commemorate Yom Hashoah. Our movement members bravely and beautifully shared the memories of their families and retold the stories of the youth, child refugees, Jewish women and the righteous among the nations in the Holocaust. We heard about how to learn from our history to bring light to the darkness and how Habonim Dror has shaped our youth in the memory of The Shoah. Here is a compilation of the pieces created by our members to honour those who survived and those we lost

Opening Statements

Good evening, and welcome to the 2020 Habonim Dror Yom Hashoah Tekkes. In these most unprecedented times, when human contact has been restricted, it gives me immense pride that the Habonim community has come together, to commemorate, but more importantly remember the Six Million lives brutally taken. Taken not because they were criminals, sinners, or threats to European society. Taken because they were Jews.

“When you listen to a witness, you become a witness…please heal the world, and never forget us.” These are the eloquent words of Holocaust survivor Judy Wissenberg Cohen, which perhaps best underpin and represent why we are here this evening.

We are here this evening, together as one, to ensure that the torch of Holocaust memory is successfully passed to a new generation, our generation, whose sincerity, idealism and commitment to fill the pages of history is remarkable.

Tonight may not be easy; tonight may be confusing; however, tonight will be inspiring. We shall hear the personal stories of those taken, told through the words of their grandchild and great-grandchild. Tonight we will bring light to that darkness that stains our shared history. Tonight we will remember through memory.

– Oliver Kingsley

This years tekkes has taken the theme of ‘Remembering through Memory’. So why this theme?

A few years ago I attended a Holocaust Memorial Day Ceremony in Manchester which will stick with me forever, and which has altered my view on Holocaust education. A Holocaust survivor stood on stage and welcomed those survivors in the room to stand in their seats. A small number of people arose and the survivor on stage reminded us that each year this number is lessening and thus each year, those around to tell their stories is depleting. He then welcomed his son and his grandchildren to the stage. His son asked 2nd, 3rdand 4thgeneration survivors – those who are the children, grandchildren and great grandchildren of survivors – to stand and he made a plea. He addressed each of us to say that that small group of people standing at the front of the room will be smaller next year and the year after. He said that the responsibility of telling our families stories has now fallen on us. This message has rung in my ears ever since, and feels all the more pressing now in this difficult time, where trips to Poland and survivors making live testimonies are cancelled. It is our responsibility as Habonim Dror to do all we can to draw attention to these stories and to take the baton that our beloved survivors are passing onto us.

So this year’s Habonim Dror Yom Hashoah theme is remembering through memory, and that is exactly what we intend to do this year and for every year to come.

You will now hear from family members of survivors who have chosen to take the immense task of carrying their grandparents, aunts and great-grandparents stories to teach the world of what happened, so we may never see a world where history is repeated.

– Ilana Finke

Remembering the Waxman Family

My nana was born in Vienna in February of 1940. At 8 days old she was removed from her parents and put into a Jewish Orphanage and in 1942 she was transported from there to Theresienstadt. 15,000 children passed through this camp and no more than 1000 survived. Being placed in a concentration camp at merely 2 years old meant that she must’ve relied heavily on the elders in the camp for nourishment and care. To this day we do not know the names or anything about the people in Theresienstadt who helped my nana survive. They risked their lives so that she could survive to tell their story.

We know very little of her time in Theresienstadt. Like many survivors, my nana rarely discussed her past. Her daughter(my mum) didn’t know she was a survivor until she was 10 years old and was rummaging through her mummy’s handbag and found her passport which said her birthplace was Vienna, Austria. Nana felt it was a private issue and it hurt her to have to remember. Her childhood memories weren’t ones of Friday night dinners with her family and playing in the park with the kids on her street. Her childhood memories were of vicious dogs that the Nazis used to control, of being hungry and being used as a pawn in an elaborate Nazi hoax when the Red Cross visited the camp.

On the 15th of August 1945, 3 months after Tereisenstadt was liberated, my nana arrived in Britain and was one of the ‘Windermere Children’. She was one of the ‘little ones’ who came over with ‘The Boys’. Having spent her first 5 years surrounded by conflict, fear, and death she had a difficult start to her time in England. This is a report on my Nana from Windermere in November of 1945:

“Judith is probably our most beautiful child to look at which is unfortunate in itself: a) because she is very conscious of the fact and b) because every visitor, whoever comes to the Nursery invariably makes a terrific fuss of her. She is very vain, spending much of her time in front of the mirror, admiring herself and arranging her hair, saying at intervals to passers-by “Am I beautiful?”. She is not very popular with the other children as she is rather an unsociable and possessive child. She is very aggressive and delights in provoking other children. She is one of the children who is most in need of an ordered and settled life”

For anyone that knew my Nana, this could not have been further from the truth as we knew her. In fact, we giggle now at this description!

My nana was adopted in July of 1947 by Rose and Louis Ingleby. She was quite understandably a difficult child who was known to break the thumbs of boys on the playground who made fun of her, she couldn’t speak English and this was the way she knew to fight back! With the help of her new family, she became a well- rounded, kind-hearted person remembered for her infectious giggle. She never lost her feisty streak and that is something I always admired of her although I’m glad she stopped breaking people’s thumbs.

Despite a traumatic start to her life, that little Viennese girl had gritty determination and a spirit to survive against all odds. She had a wonderful marriage, had 4 children, 14 grandchildren, and 4 great-grandchildren. She made new memories.

I will leave you with one last thing she always used to say.. ” You have to be born lucky an I wasn’t born lucky” … try and remember that! Thankfully we were all born lucky.

– Millie Collins

Remembering the Finke Family

I am the granddaughter of Heinz Wolfgang Finke, who arrived in Wallsall, England on the Kindertransport, never to see his parents or brother again. I am the great Niece of Ursul and Hans Finke who, through their inconceivable strength, survived circumstances no person could truly understand.

Today I will tell the story of my Aunt Ursul who was born in Berlin in June 1923. Ursul’s story is by no means ordinary. She has inspired my life and shown me the strength of women and the strength of humanity. To say I am defined by her memories, would be an understatement.

When my Aunt was 20 years old she begrudgingly moved out of her parents home and became what was known as an ‘illegal’ so as to protect herself. Soon after, her parents were packed onto trains from Silesia to Auschwitz and she never saw either of them again. One week later, her brother Hans was sent off on that same train, but Hans survived to tell his story. He will forever be a living miracle, a man so determined to live that he survived 2 concentration camps and the death march by living for 10 days off the snow, and who created a new life for himself in America.

Whilst Ursul was living illegally, the Gestapo found her out. The plan was to send her to a Gestapo holding camp but one of the officers took a liking to her. He agreed that she would meet with him and present him with her papers to prove she was not Jewish, she agreed. They met the following day, and as he was so taken by her, he agreed to silence the charges against her if she came to his home while his wife was away. It was clear that she needed to get away.

She got word that there was a family willing to help her in return for her working and so she ran. For a whole year, my aunt lived a fairly normal life, working in a lending library under a fake identity and living with the Daenes family, until one day on her way home from work she was grabbed by an officer. To her surprise, it was the same Gestapo officer that she had tricked and run from the year before. He dragged her to his commanding officer and she screamed for mercy. Seeing that her choices were limited, and having vowed she would not be taken by the Nazi’s, she threw herself in front of an incoming train.

Her story did not end here. Ursul was taken to the Jewish hospital where following normal procedure she would have been patched up and sent to Auschwitz. However, Dr Lustig took pity on her and instead she became the subject of medical testing. For 4 months she was pumped with testing drugs, she had a temperature of 40 degrees and lost 40 pounds. In April 1945, when the air raids worsened, she was left in the basement of the hospital chained to her bed. One month later on the 8thMay, the hospital was liberated and at a mere 31 Kilos, my great aunt Ursul was saved.

She was unable to leave the hospital until the month later and until the day she died, had to have continuous medical treatment on her leg as the damage was irreparable.

After the war, she passed her masters tailoring exam and gained her independence. She never left Germany as it was always her home. She did not marry nor have children, instead she created a community in a place that once so desperately tried to discard her. When my father attended her funeral he described hundreds of people. This is a women who lost her whole family, everyone but her brother and cousin and who persisted in the place once full of such hatred, to create community so strong that hundreds attended her funeral.

I will never know what gave her, Hans or my grandpa their strength, I can only hope that it is something that I have inherited. I feel honoured to be able to tell their stories so that Jewish youth can be empowered and so that their suffering was not for nothing.

– Ilana Finke

Remembering the Kuranda and Kerekes Family

As someone who was brought up in a family so terribly haunted by the events of the Holocaust it seems only right that we have come together as a Habonim community, to commemorate, but more importantly, remember those lost through their memory.

Trying to understand the horror that is the deaths of 6 million Jews is impossible. Trying to comprehend why the greatest atrocity of our history took place is impossible. But bringing back the humanity, dignity, and memory of those who were taken, is not impossible, but our duty.

My great-grandpa Paul Kuranda, a man of immense dignity and kindness, lost his entire family during the horrors of the Holocaust. His mother Regina Kuranda, his father Leopold Kuranda, and his grandma Olga Kuranda were all brutally murdered in Theresienstadt, Czechoslovakia in 1942. It saddens me to think that my great-grandpa, aged 21, was forced to wave goodbye to his loving family, who were never to be seen again.

Despite the great sadness, we must bring light to this darkness. My Great Grandpa came to the UK, broken, confused, and lost. He came with the clothes on his back, and the pennies in his pocket, and yet he married my Great Grandma, Elizabeth Kerkes, who also lost her entire family, built a successful business and created a life for himself. When he died aged 100, he had four grandchildren, and eight adoring great-grandchildren.

The pain and struggle endured by my family, on both my mum’s and dad’s side, during the darkest of times puts everything into perspective for me. Today I am proud and humbled to remember my ancestors through bringing to life their memory. Thank you for this opportunity, and as we stand here as one united Habo community, may we never forget their pain, their suffering, but most importantly, their memory.

– Natasha Kingsley

Jewish Responsibility over Refugees – The Muchanimot

Today I’m going to be speaking on behalf of the muchanimot shichva in relation to how the holocaust has influenced us as Jewish people to take action towards the refugee crisis in modern day.

In 1939 Nicholas Winton, aged only 29, organised trains out of Prague to allow the escape of 669 Jewish children, via kinder transport during the Holocaust. He said nothing about his righteous deed for around 50 years before his wife found his scrapbook containing a record of names and pictures, highlighting how his actions came from the good of his own heart rather than to seek recognition and appreciation. Winton received an American Congressional resolution as well as honorary citizenship of Prague. He had streets named after him, and statues erected in his honour. In 2003 Queen Elizabeth II knighted him and in 2010 he also received a Hero of the Holocaust medal.

We have found stories of two people who were helped by Nicholas Winton, who were able to go on and live important lives that they otherwise would not have been able to.

The first is Anita Grosz, the daughter of a Winton child.

“My father, Hanus Grosz, and his brother, Karel Gross, from Czechoslovakia, were saved by Nicholas Winton. My father was 15 and my uncle was 13 when they left for England. Their father died in Terezin and their mother was killed in Auschwitz.

The boys were first placed on a farm in Warborough to do manual labor, followed by a series of farm training camps. My father went to Czechloslovakia after the war to look for family. In Prague there were boards where you could search for family names, but he didn’t find anything. In 1948, he started medical school at the Welsh National School of Medicine where he specialised in psychiatry.

He felt there was a lot of anti-semitism in the English medical field, so around 1959, he moved to Einstein University Hospital in New York to receive training in neurology. He went on to teach Psychiatry and Neurology at the Indiana University School of Medicine. After retiring he focused on helping victims of crime and people struggling with addiction.”

The second is Shulamit Amir, a Winton Child.

“I was saved by Sir Nicholas when I was 12 years old. My mother sent me on the train that left Prague on May 13th, 1939. I never saw her again.

I spent the war years in London, where my father was waiting for me. He made his way to England, hoping that my mother would manage to get me out.

When I finished school, I went to teacher training college. I moved to Israel in 1947 to marry a man who was serving in the Jewish Brigade, which was part of the British Army. We have four children, 10 grandchildren and two great-granddaughters.”

Many of us have ancestors that survived the holocaust due to kinder transport and the selfless acts of many people including Nicholas Winton and those who were labelled righteous among the nations. If these individuals didn’t take the risks that they did, many of us wouldn’t be here today and Judaism as a whole may have been greatly affected. Therefore, as todays youth we should all be taking an active role in helping those in need around us such as refugees so that they can have the same opportunities that we’ve been blessed with.

So what is a refugee?

According to the UN refugee convention, the definition of a refugee is someone who “due to a well founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, being a member of a particular social group or political opinion outside the country of his nationality is unable to or unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

The situation in Europe during the 1940s in regards to the Jewish refugee crisis isnt that dissimilar to the refugee crisis that we are facing today. We must understand the fear that our ancestors faced and their desperation in order for us to take action today to help those in very similar situations today. Crucially refugees are people just like ourselves who have lives to live and families to care for. Humanity is the human race which includes everyone on earth and if we can’t help each other then how can we expect to receive help ourselves in times of need and take those steps forwards in life that are necessary to bring us all together.

We wanted to finish with this inspirational quote by Nicholas Winton. “If something’s not impossible, there must be a way to do it”

– Lottie Blankstone, Alicia Harris and Max Jacobs

Female Experience of the Holocaust – The Shnatties and Shnotties

We rarely hear stories about the exploitation of women in the Holocaust. For me, this isn’t very shocking. Just as women are silenced today about their experiences, of course the case was the same during the holocaust. Dr Rochelle G Saider – founder of the Remember the Women Institute says there are multiple reasons why the topic of sexual violence during the Holocaust has received little attention. For one, male survivors and historians largely shaped the narrative. This is by no means an attack on male survivors – their stories are just as valid and important, but men and women had very different experiences, as indisputably gender played a huge role.

It has been reported that 50-80% of the S.S troops and police units that operated in Eastern Europe were guilty of sexual abuse towards Jewish women. These soldiers and police did this not only for their own sexual pleasure but also to exert their dominance over the Jewish people and dehumanise them. During the holocaust, the Jewish people were seen as incapable of human emotion, thus these crimes didn’t matter – the women were toys – purely objects to be used as weapons of war. Their goal was to humiliate those who were ‘inferior’ to them and prove who really was the superior race – and in a lot of ways the superior gender too. The S.S soldiers would kill the women almost immediately after assaulting them because in the early 20th century, if a German person had sexual relations with a Jew it was considered racial defilement and was punishable by jail or death.

There are many stories in which in order to survive, women had to enter sexual relations with guards in exchange for food and other necessities. It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like for these women. The disempowerment for anyone in a concentration camp is massive but for women was tenfold. How these women coped is something I don’t think I’ll ever understand. They inspire me beyond what I can articulate. They were helpless, objectified and abused. Yet, sex crimes weren’t even classified as war crimes until the 1994 Criminal Tribunal of Rwanda.

These barbaric acts are hard to fathom and even harder to hear, perhaps one of the reasons these stories are so taboo. But these women should never be silenced and it is never too late to tell their stories and keep their legacy alive. We must also remember it’s not all doom and gloom regarding women in the Holocaust – take Chavka Folman for instance. She was a true heroin who in addition to engaging in resistance operations against the Nazis, smuggled false documents and newspapers, food and weapons into and out of the ghetto. She travelled from ghetto to ghetto, constantly changing identity and bringing news, hope and basic necessities to Jews who were completely cut off from the outside world.

But by talking about the women who had painful experiences, we hold the guards and officers accountable – even if it is over 80 years later.

Although we cannot empower these same women today, together we can tell their stories on their behalf, empowering their memory and Jewish women everywhere. Any woman with the courage to speak up about her experiences, gives other women the platform to speak about theirs. As a collective, we can keep building, making the platform higher, therefore the volume louder. In my view, this is the best legacy they could have left behind.

– Millie Bickler and Danele Evans

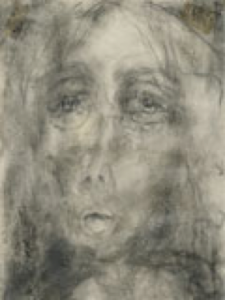

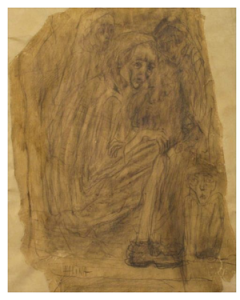

‘Women in Birkenau Camp’ by Halina Olomucki, drawn secretly while imprisoned in 1945.

”While I was in Auschwitz-Birkenau someone told me, ‘if you live to leave this hell, make your drawings and tell the world about us. We want to remain among the living, at least on paper.” – Halina Olomucki, ‘Why?’, Germany, 1945.

The Righteous Among the Nations – Shlav Bet Kvutza

This is a compilation of texts that I gathered from the Yad Vashem archives about righteous among the nations.

The Righteous Among the Nations, honored by Yad Vashem, are non-Jews who took great risks to save Jews during the Holocaust. Rescue took many forms and the Righteous came from different nations, religions and walks of life. What they had in common was that they protected their Jewish neighbors at a time when hostility and indifference prevailed.

The German decision to exterminate all of European Jewry was made at the highest levels – by Hitler himself – around mid-December 1941. Holland were one of the most efficient countries at adopting Hitler’s poisonous regime and ideology.

The character of the German regime in Holland and its tremendous efficiency made it more dangerous to rescue Jews in Holland than in Belgium or France. Anyone caught helping Jews in the latter countries would suffer a relatively mild punishment, but in Holland he or she was likely to be executed or sent to a concentration camp, where the chances of survival were very slim. The German and Dutch police conducted searches for hidden Jews and gave informants a sum of money for every Jew caught with their help. The German police also enticed Jews to leave their hiding places with false promises to save them from deportation.

Nevertheless, initial signs of spontaneous aid to the Jews occurred just days before the first transport from Amsterdam to the Westerbork transit camp. Cor Basiaanse, a young woman from the town of Utrecht, traveled to Amsterdam, collected a number of children from her parents’ home and brought them back to Utrecht, where she hid them among a number of families. Four organizations specializing in the rescue of children soon emerged: a group of students from Utrecht, a group of students from Amsterdam, a Christian organization called “Friends International,” and a group of devout Christians connected to an underground newspaper. Together these four groups saved some 1,100 Jews, some 90% of which were Jewish children hiding across the country.

Significantly, the students from Utrecht received support from the archdiocese of Holland, J. de Jong, residing in the city. Not only did he allow them to use his safe for storing documents, he also gave them financial aid and requested that Dutch bishops contribute towards the holy cause of saving Jews. This was extremely important. The archdiocese had objected to the Nationalist–Socialist movement since the 1930s, forbidding Catholic believers to join. This resolved stand of the religious leader influenced his subordinates, and many Jews were hidden in areas inhabited almost exclusively by Catholics. In one case, a Catholic priest in a small village was executed for saving Jews.

The religious authorities were a decisive influence in many cases, especially in the villages and small towns where residents of the homogeneous Catholic communities were generally aware that certain families were hiding Jews. Their religious and social unity prevented informing to the official authorities, a widespread phenomenon in the larger cities. One example of this was the town of Nieuwlande in the east of the country. A local resident, Arnold Douwes, together with a young Jewcalled Max Leons, organized the transport of Jews from the west, where they found refuge among some 200 families.

The Westerweel group, a well-known underground group named for its charismatic leader, managed to save hundreds of young people. In August 1942, rumors that the German police were planning to arrest more than 50 young members of the “Aliyat Hanoar” youth group flooded the area. Answering a plea by the young halutzim (pioneers), Joop Westerweel and his companions found hiding places for all of them within a few days. From the beginning, the two groups – the Westerweel group and the halutzim – enjoyed a strong bond. The latter, a Jewish underground group headed by Shushu Simon and Menachem Pinkhof, worked tirelessly with the Westerweel group to bring some 150 halutzim from Holland to France. Their real aim was to get to Eretz Israel, and some 60 achieved this while the war still raged in Europe. At his departure from the first group at the foot of the Pyrenees, Joop Westerweel gave an emotional address in which he asked them not to forget their friends and those who had suffered under Nazi rule, and to safeguard the freedom of the new Jewish nation in Eretz Israel. Westerweel was arrested in March 1944 trying to help two young Jewish girls flee across the Belgian border. Despite cruel torture, he refused to reveal anything about the activities of the group. He was executed on 11 August 1944.

– Karl Adelman

Harnessing Light from the Darkness of The Shoah

As a History student at University, I am occasionally surprised when Jewish history intersects with my degree. The Shoah was a notable example when discussing the role of objectivity and truth in history, especially the role historians play in creating narratives about the past: there is no one objective narrative of the past waiting to be discovered, rather a series of conclusions that can be drawn from the available facts. Trying to separate ourselves from this process is futile – every time we think about the past we are imposing a series of assumptions at every level. It has become common to state that Jews don’t have history, rather we have memory, but we must also never forget that that memory comes from a series of choices. We choose how we remember, what we remember, when we remember, who we remember, why we remember. Yom Hashoa is the perfect example of this: we as Jews choose to commemorate the Holocaust not on the date we were liberated by Russian forces at Auschwitz as on the International Memorial day, bur on the day when Jews themselves chose to resist through the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. At Habonim Dror we choose to teach our chanichimot and madrichimot to face these choices, and to recognise that it is our responsibility, as today’s Jewish youth, to choose to carry forward the legacy of the Holocaust into the next generation. We choose to remember the victims as people, and not just numbers. We choose to focus not only on the intense darkness of the Shoah, but on the brief moments of light amongst that darkness, the moments that reveal the resilience and courage of the Jewish spirit and the human soul. We choose to remember our Dror forebears, whose ideals of rebellion and resistance can inspire a better future that they never lived to see.

– Harrison Engler

What Habonim Dror has learnt from The Holocaust

I wanted to share with you a story from when I went to Poland on Shnat in 2016. As we arrived at Majdanek I fell silent. Walking around the death camp my madricha spoke about how the Jews were stripped of all their clothing, their hair, their jewelry and ultimately their individuality. Now they were just one group, they were the Jews. That moment really stuck with me because yes, once you strip everything away we are Jews and we are all here at this tekkes because we are Jewish, but there is more to each of us than that. We are intelligent, we are strong, we are funny, we are caring and we are anything we want to be. All those who perished in the holocaust were also intelligent, strong, funny, caring and so much more but were without all the privileges that we have today. We have the privilege to have an opinion, to debate, to protest, to vote. And If you aren’t using that privilege for good then what is it really for? We owe it to all of those who died in the holocaust be it the Jews, the women, those who identified as non-binary, homosexuals. We owe it to those who are a minority today who need our help and our voices to continue fighting for good and for their rights.

Habonim Dror has acknowledged the privilege we now have and the holocaust has been shaping the way we educate. We are not only speaking about Jewish identity and what Judaism means to our 400+ individual members. We are talking about co-existence, we are learning about feminism, we are getting clued up on different cultures, we are debating socialism, we are expressing our Zionism and we are realising just how powerful the youth of today are.

For years Habonim Dror has made holocaust education a high priority to make sure that we truly never forget what happened to our ancestors. As I mentioned before, on Shnat you visit Poland as a kvutsah to learn about how the youth movement resisted and helped in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. We are the only movement to run a machaneh entirely about the holocaust and anti-Semitism. Last year on machaneh when Habonim Dror turned 90 we made sure that all shichavot had a peulah about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising as it is a huge part in our history.

To be honest I don’t know another movement that does what we do and helps shape Jewish identity the way that we do. We have had members go on to set up J-Socs at their university, attend anti-semitism rallies, be presidents of J-Soc committees, go on to create charities for minorities and even go on to be the current CEO of March of the Living UK.

Right now, during the covid-19 pandemic we aren’t slowing down on our activism. We have set up different volunteering opportunities with different Jewish charities around the UK. Some of you are shopping for those who can’t leave the house, some of you have a buddy who you call once a week and check up on them to see how they’re doing, some of you have written or drawn pictures to those who spent both Seder nights alone this year and some are currently writing about the importance of Israel and what it means to them for Yom Ha’atzmaut to send that out to the elderly as well. Social activism has always been a part of this movement because of the care and responsibility we have over each other as Jews and we know full well what happens when nobody speaks up for other minorities. I can only wish that for the next 90 years of this movement the strength, kindness and responsibility will continue to grow.

– Jake Fenton, Mazkir 5780

Closing Remarks

This evening we came together as a united community to remember the darkest moments of human history. It is ok to be sad, to be angry, or even confused. But one thing that I hope all of you feel this evening is pride. Proud of our people’s resilience, proud of our people’s strength, and proud of our people’s future. For there may have been dark days, but in the end, good triumphed over evil, and the Jewish spirit prevailed.

Six million is a vast number, a number so inhumane and incomprehensible, but what we have done this evening has brought life, understanding, and humanity back to that infamous figure.

Tonight we have heard of the bravery and resilience of Judith Waxman, the suffering and strength of Ursul Finke, and the dignity and warmth of Paul Kuranda. We have heard these stories not through the passages of history but through words of their descendants; living breathing proof that the mission of Nazi German failed. Failed to dampen the Jewish spirit, failed to erode our sense of belonging, and failed to confine our people to the passages of history.

Tonight was not just about commemoration; tonight was also about bringing light to the darkest parts of history. We have learnt about how simple acts of defiance give people their humanity. We have learnt of the Jewish responsibility for refugees and victims of other genocides. We began to understand the horrors, so many women had to endure during the pain of the Holocaust. We have shined a light onto the bravery of those who stood up to the forces of evil, The Righteous Among the Nations. And we have been inspired to harness light from the darkness of the Shoah.

I’d like to end with the words of Anne Frank, a girl who despite all the suffering remains an inspiration to us all.

In spite of everything, she wrote, I still believe that people are really good at heart. I simply can’t build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery, and death. I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever-approaching thunder, which will destroy us too, I can feel the sufferings of millions, and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right, that this cruelty too will end, and that peace and tranquillity will return again.

May we never forget their memory, and may we all have the wisdom to see, the courage to want, and the power to act.”

Thank you.

– Oliver Kingsley

Recent Comments