‘Tit-illation’; Double Standards and the Censorship of the Female Breast

I’m sure we’re all familiar with the #FreeTheNipple movement – it’s slogan is often the butt of a joke or the half-baked battle cry of someone trying to mock modern Western feminism’s current focuses. On the surface, I understand – why are we putting so much focus on something as stupid as a nipple when there are women around the world being denied fundamental human rights to education, autonomy over their bodies, fair wages and so much more? However, I also understand that the reason this is people’s “go to” feminist slogan is symptomatic of the issue at hand. Breasts (more specifically female breasts) are taboo, and therefore titillating – if you pardon the pun – so of course this gets attention. But who decided they were taboo in the first place?

To explore this further, last year for a university research project, I decided to examine the different ways breasts are depicted in magazines. Through examining the covers and contents of a range of contemporary men’s and women’s magazines, I compared the different ways breasts are portrayed, depending on the gender of the person they belong to, and what the images reveal about cultural attitudes surrounding sexuality, modesty, and censorship. I then explored historical and cultural attitudes towards breasts in different places, navigating the dual purposes of breasts as both sexual objects of arousal and stimulation, and nurturing organs meant to sustain life through breastfeeding.

In doing so, I came to understand that the censorship of female breasts is part of a larger attempt to control women, their bodies, and their sexuality in order to serve male needs. The call to #FreeTheNipple is not a distraction, or a separated issue from a woman’s right to autonomy, education and freedom, but rather deeply connected to all of the above in an attempt to liberate women from the censorship or control of patriarchal structures. But let’s not skip to the ending yet – because my findings were particularly juicy.

What did the magazines have to say?

The overwhelming majority of images of women, bar only men’s pornographic magazines, did not show exposed female nipples, but did show women and female breasts in a variety of evenly divided sexualised images (eg. Miley Cyrus posing seductively on Wonderland, nude model on Tattoo Life with long hair covering bare breasts) and non-sexualised images (eg. Joanna Lumley on Good Housekeeping, Alex Jones on Prima). In images of women, the more breast or cleavage shown, the more sexualised the posing and image tended to be.

Images of men were also evenly divided between sexualised images (eg. muscular topless men posing on covers of Flex and Muscle & Fitness UK, Antoni Porowski topless on Gay Times) and non-sexualised images (eg. Dave Grohl on GQ), but with the notable difference of toplessness exposing male nipples and Vogue Hommes showing a topless male model in a non-sexualised manner.

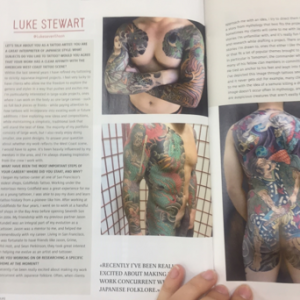

After examining magazine covers as a general representation, I also compared the depiction of male and female bodies within the magazines. One stark contrast appeared in Tattoo Life, where all models were almost fully nude to show their body art, but the women were posed in lingerie with sexualised poses and facial expressions, whilst men were photographed neutrally and almost clinically, without showing their faces. For the men pictured, the image was about appreciating the tattoos and the art form, but for the women it seemed to be much more about a sexualised fantasy.

The most explicit double standard towards male and female nipples was presented in Heat UK 15 May 2018. In the same magazine that a shirtless Ryan Reynolds is praised for his ‘flawless appearance’, singer Charli XCX is shown with the caption ‘Stock Falling: Modesty, Charli XCX appeared on stage […] only to have her boob pop out. She apologised on Insta, but we’d already seen it all.”’, shaming her and explicitly stating that even the accidental exposure of one of her breasts whilst performing reduces her value and requires public apology for her indecency.

Eeshk that’s not great… but what does the rest of the world / history have to say?

In Yalom’s book ‘A History of the Breast’, she remarks upon how breasts are seen as ‘crowning jewels of femininity’, that play an essential role in performing femininity and female heterosexuality, with their sexualisation central to female attraction, flirtation and sexual activity. Despite not being genitalia, breasts are understood in oversexualised, patriarchal Anglo-American society to be inherently sexual, and as such are ‘treated as sexual organs’, in the way that they both arouse sexual excitement and elicit moralised censorship.

This phenomena is not necessarily natural, but rather a product of patriarchal social construction, as shown by changing cultural norms in different regions and time periods. For example, in Europe in the sixteenth century, it was fashionable for women, from pauper to royalty, to wear gowns that fully exposed their breasts, and exposed breasts feature regularly in non-sexualised contexts in Renaissance paintings. An interesting parallel would be to the sexualisation of women’s feet in Chinese culture to that of women’s breasts in Anglo-American culture, highlighting the arbitrary nature of the focus of heteronormative male desire. To people questioned in Mali, where breasts’ sole perceived purpose is to feed infants, the notion of adult men finding female breasts sexually attractive is seen as unnatural, perverted behaviour.

Even within contemporary Western society there is strong variation in attitudes to exposing female breasts, with topless sunbathing normalised in much of western Europe. The modern Anglo-American consensus on the innate sexuality of breasts has puritanical religious origins, and works to sexually objectify women’s bodies, which is the the primary process of the subjection of women, and essential to patriarchal constructions of power.

Research studies have found that exposure to sexually objectifying images of women’s bodies, and particularly breasts, have been found to condition men to adopt traditional gender ideologies and to be more accepting of women as sexual objects’, so the prevalence of such images in everyday pop culture, mass media and advertising, reinforces heteronormative sexual scripts of men as active ‘sexual agents and initiators’, and women as passive ‘sexual objects and gatekeepers’.

Breasts in these images are seen through the male gaze, not sexual in their potential for self-stimulation and sexual enjoyment for women, but in their role in ‘animating male desire’, and as objects of male pleasure, hence the discourse of breasts as an unfair “distraction” for men in various contexts such as school or the workplace.

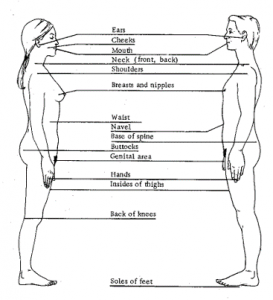

Whilst areolas are understood anatomically to be erogenous zones for men and women (notably alongside earlobes and inner arms which are not publically censored), are the focus of sexual acts for both men and women, and are known to ‘develop from the same foetal tissue and have connections in the sexual brain’ and, the male breast/nipple seemingly has next to no sexual connotation and can be exposed publicly without evoking emotional upset.

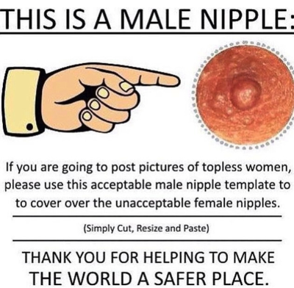

In contrast, the display of female breasts is seen as inappropriate, vulgar and pornographic with particular effect if the nipple is present, so is illegal in public in most US states and the UK, and is censored on popular social media sites Facebook and Instagram. Feminist activists argue that allowing the whole female breast tissue to be shown but not the nipple is nonsensical, and perpetuates the unnecessary sexualisation of breasts by making them taboo and therefore titillating, whilst questioning why excessive violence is acceptable and uncensored in media when breasts are not.

Hold on a minute – but what about what breasts are actually for?

I wanted to explore if this sexualisation and subsequent censorship affect what we have become uncomfortable seeing. When collecting my research data, I noted not only what was depicted, but also what images and narratives were omitted; none of the images of female breasts showed a woman breastfeeding, the primary biological purpose of mammary glands. The constructed image and perception of breasts is that they ‘exist for men’s erotic enjoyment’, so non-sexualised nudity is perverted and made sexual. Society is offended by breasts that do not serve the male gaze or fulfil their “purpose” as objects of male pleasure, as evidenced in studies that found that ‘endorsing ideologies [constructing] women’s bodies as sexual objects may make men less comfortable accepting reproductive aspects, such as breastfeeding’.

This discomfort is arguably also symptomatic of the pressure to conform to either of the opposing archetypes for women, the madonna and the whore, in which the mother is the madonna, and the “good” maternal body is not commonly believed to be simultaneously sexual (despite the obvious facts of human reproduction). Breastfeeding does not comfortably fit the narrative of the ‘woman-as-(hetero)object’. Much as women are sent contradicting messages about using their breasts to attract sexual desire whilst also being shamed for sexual liberation, they are sent equally confusing messages about breastfeeding; in that “it’s the best thing for your baby”, and so women who don’t or can’t are shamed, but also “don’t do it in public because it’s sexual and offensive”.

Media depiction of breastfeeding mothers is often met with intense backlash or pre-emptive censorship, with the June 2015 Elle Australia cover of a breastfeeding model sent only to subscribers, and an alternative photograph sold on magazine shelves, and the backlash to the famously controversial image on the 2012 TIME cover of a woman breastfeeding her toddler, which because of how ingrained the sexualisation of the female breast is, the image elicited anger likening the image ‘to pornography and the act of breastfeeding to incest’. Sadly, there is plenty of research showing how shaming of public breastfeeding discourages mothers from nursing, despite the plethora of health benefits for the mother and infant.

So… to free or not to free?

It seems clear that perpetuating the perception of the female body as inherently sexual works to solidify systems of patriarchal power through objectification, and it is my opinion that normalising non-sexualised exposure to the naked female form will be a positive step towards achieving true gender equality.

To answer the question to free or not to free : do whatever the hell YOU want with YOUR body – and do your best to facilitate others ability to do the same. Because even if you have absolutely no desire to free your own nipples, in the wise words of Audre Lorde “I am not free whilst any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.”

Becky Tuck – Rakezet Hadracha & Chinuch

Recent Comments